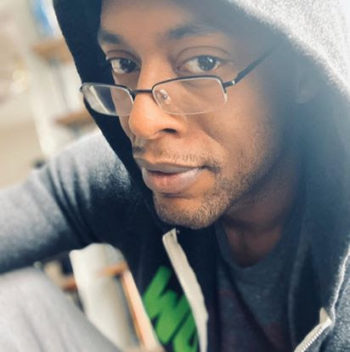

by Delma Jackson III

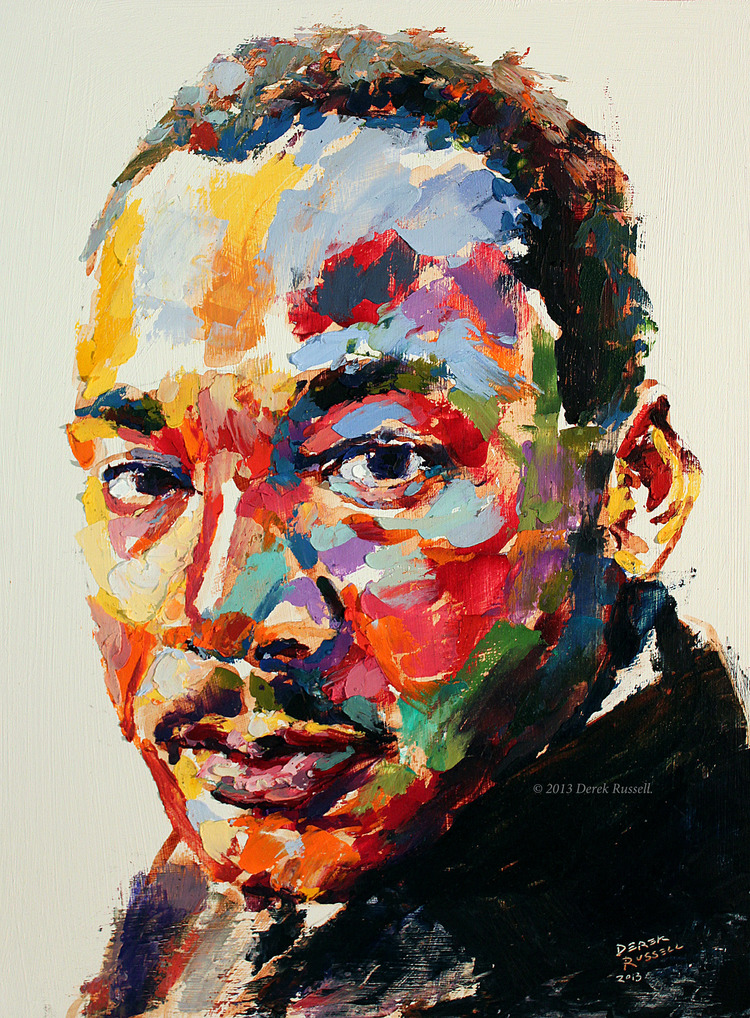

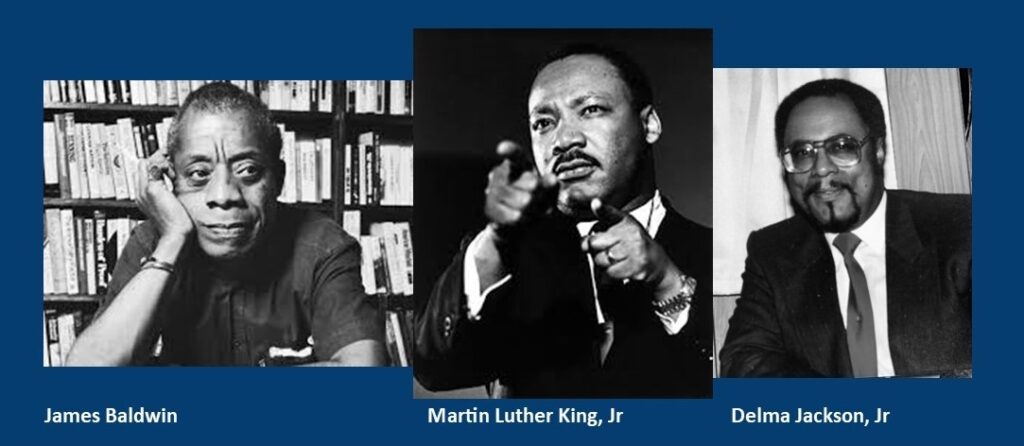

“It takes strength to remember, it takes another kind of strength to forget, it takes a hero to do both. People who remember court madness through pain, the pain of the perpetually recurring death of their innocence; people who forget court another kind of madness, the madness of the denial of pain and the hatred of innocence; and the world is mostly divided between madmen who remember and madmen who forget. Heroes are rare.”― James Baldwin, Giovanni’s Room

“Groups are more immoral than individuals”1

– Martin Luther King Jr., Letter from a Birmingham Jail

“Chillin’ like a white man.”2

– Delma Jackson Jr.

It’s hard to admit I’m exhausted when I feel like I have no legitimate reason to be. It’s hard not to constantly beat myself up over what I think my ancestors would do if they were in my place. It’s hard to hold self-care in the left hand and unwavering commitment in the right. Like the 80s/90s movie trope of a street corner hustler, it’s easy to lose track of which hand is holding which card. So I take on more projects. Hold space for more conversations. Look for ways to hold what’s immediately in front of me even as the apartheid in Gaza blooms and the parallels feel so painfully obvious as they further delineate between who matters and who doesn’t.

What’s both exhausting and fascinating is watching the US eat itself alive as Trumpism further exposes a large swath of the population happy to twist itself like caduceus to ensure American pluralism remains synonymous with assimilation. I’ve lived just long enough to watch the US go through yet another cycle of social movement and backlash–a cycle that repeats itself throughout this country’s history over and again. I imagine my elders from the 60’s can relate to this feeling. I imagine the 40’s and 20’s saw similar skepticism arise among black and brown folks as they watched the tide of social justice flow then ebb–hope giving way to cynicism.

I’ve lived just long enough to remember our collective shock when those who beat the blood and congestion out of Rodney King walked out of courtroom free men. We’d been telling that same old story for years but THIS TIME, it was on tape. It never occurred to my young self that some would enjoy the footage–my Jordan Peele; their Zack Snyder. I remember watching Black rage embodied as LA burned. I remember how many politicians (white ones specifically–but not exclusively) openly condemned the riots only to openly celebrate (without irony) Martin King and the 30th anniversary of the passage of the civil rights act a few years later. They can only celebrate violence when they see themselves as the protagonist: from the Boston Tea Party to January 6, 2021.

I remember sitting in a theater and watching Spike Lee’s, Malcolm X with my father. I remember leaving feeling empowered, seen, and spoken for in a way I’d never felt before. I remember the profound relief of knowing I wasn’t crazy. I remember watching the coverage of the Branch Davidians in Waco, TX–increasingly enraged at how this predominantly white, heavily armed group could succumb to violence at the hands of the state and it be called a tragedy, but when lone, unarmed Black folks were maimed and/or killed at the hands of the state, it was justice. I remember learning that Nelson Mandela was sworn in as South Africa’s first post-apartheid president.

I remember the rampant Islamophobia across the US on full display for years after September 11th, 2001. I remember how the xenophobic othering of film and TV in the 80s and 90s came full circle and Islam was held responsible for the actions of a few people in a way that Christianity never was.

I remember watching Barack Hussein Obama take the oath of office as the first Black US president eight years later–the same year social media saw a huge upswing in usage. For the first time in human history, millions of people could share their experiences with one another in real-time. So I remember the inevitable rise of documented police abuses and killings across Black and Brown communities around the country. I remember the rise of activism from #BLM to #theArabSpring, to #Metoo, to the #UmbrellaRevolution.

During the Obama years, each new documented case of police murders of unarmed Black folks –each new say their name hashtag, I had the sinking feeling that two distinct camps in white America perceived “change” and both were going to lose their collective minds. The “left” would rest on their laurels–believing they’d accomplished the impossible and their work was done. The “right” would feel called to re-assert their dominance and put everyone back into their respective places. The two sides, and their equally misguided perceptions about the world would trap everyone else in the middle.

Despite knowing better, this work can often feel isolating. Feeling isolated can make planning for the long term more difficult. I’d love to take lessons from the right, who over the course of 30 years, leveraged spaces like the Federalist Society to move SCOTUS to the right. However, it is much easier to plan that far ahead when you’re safe, resourced and clear that your “fears” are as manufactured as a Tesla.

However, it’s much easier to plan that far ahead when you’re safe, resourced, and clear that your “fears” are as manufactured as a Tesla.

The most exhausting part: only one half of white America appears unafraid “of the word tension.”3 I often suspect it’s the half who participated and or supported the riot on the capital.

Then there’s the well-meaning but completely clueless “progressives.” The ones King noted were too often, “more devoted to order than to justice.” You’re therefore always pulling double duty…trying to convince, cajole, force one side to stop killing you, while trying to get the other half to do more than have you over to the house, march alongside you while picking ethnic food out of their teeth, and calling you every other day to run some anecdotal shit past you to double check they’re still on the right side of history. This is a deeply disturbing take on justice, a “[s]hallow understanding from people of good will” which often proves “more frustrating than absolute misunderstanding from people of ill will.”4

Add gender and/or sexuality into the equation and the exhaustion gets compounded. I can’t help but think Black women must be asleep on their feet most days–like the protagonist in a Spike Lee joint–pulled forward and disembodied. I wanna nap just thinking about it. What does it take to navigate a population of Black men who’ve completely accepted notions of gender created and upheld by the very white men they often claim to distrust.

Baldwin was right. We need heroes. Not individuals wearing capes, but whole communities of people who can and will take up the cause when our kinfolk need to rest.

Baldwin was right. We need heroes. Not individuals wearing capes, but whole communities of people who can and will take up the cause when our kinfolk need to rest. Communities that can remind us of the differences between resting and quitting–between remembering and obsessing. This approach implores us to move away from the westernized–single hero narrative and embrace something bigger than ourselves. It implores us to take seriously the ongoing backlash against perceived progress by those whom over half the country never wanted to embrace in the first place.

We live amongst a population of people who never accepted pluralism as ideal. The civil war wasn’t won by the north. The civil war ended in a stalemate and the two populations have been stuck in a proxy-cold-civil-war ever since. We live amongst people on the right and left who never accepted the idea that anyone other than white cis-gendered men should be at the helm of our collective destiny. They can’t be blamed. Half their ideas are captured in the founding documents.

So yeah…stay or leave. Sink or swim. The constant pressure from within and without is daunting. The sheer number of us whose primary concern is making it from one day to the next is overwhelming. The number of progressives who will come for your cancellation if you don’t use the most updated language is real. The number of us who are often on the verge of crying is real. The number of us who come from the trauma of poverty is real. The journey from surviving to thriving is filled with pit stops along the way; realizations, remembrances, severings, and reconnections. Learning how to do that in community with others in service of building something new is by definition exhausting.

That said, I’m giving myself permission to be tired. I hope you do too. We need our rest. Women, and BLACK women, specifically…I’m looking at you. Go ahead. Take my father’s advice and see what it feels like to “chill like a white man.” I’m cheering for all my life-ers out there.

Hopefully, I’ll see you around this year–rested and ready to dream.

1King was referencing Niebuhr, Reinhold who wrote, Moral Man and Immoral Society: A Study in Ethics and Politics, 1932

2When I would ask my father what he was up to, he’d sometimes respond with this line.

3King, Martin Luther. “Letter from a Birmingham Jail,” August 1963.

4King, Martin Luther. “Letter from a Birmingham Jail,” August 1963.

Delma Jackson is a Senior Fellow with CWC and creator of the Dive in Justice Podcast. His focus is on facilitating system change in institutions through transformative practice and the power of story. He received his undergraduate degree in African-American Studies and Psychology, and his Masters in Liberal Arts with a concentration in American and African American Studies at the University of Michigan. He regularly lectures on a variety of socio-political topics with a special emphasis on intersectional approaches to social justice.